I have a list of blog topics outside of the walks and folklore that I write up. Often, these fall to the bottom of the priority list and of those, this one, was the lowest by far – that was until I had to remove a tick from myself at the end of the last walk I completed and now here I am, writing about ticks and Lyme disease. I’ll ne honest, this isn’t the most pleasant topic, but it is important.

What are Ticks?

Just to add to their fandom, the tick is a relative of the spider. There are over twenty species in the UK, found across the UK, and are not just confined to the countryside but are abundant in our cities also. They are small, and can be as small as a poppy seed and as such, can often go unnoticed until they do what they do and swell with blood.

There are many different species of tick living in Britain, with each species having their own preferences to which animal’s blood they prefer to feed on. Most pertinent to those of us reading this blog, the one most likely to bite humans in Britain is the Sheep tick, or Castor Bean tick, which despite its name, the sheep tick will feed from a wide variety of mammals and birds.

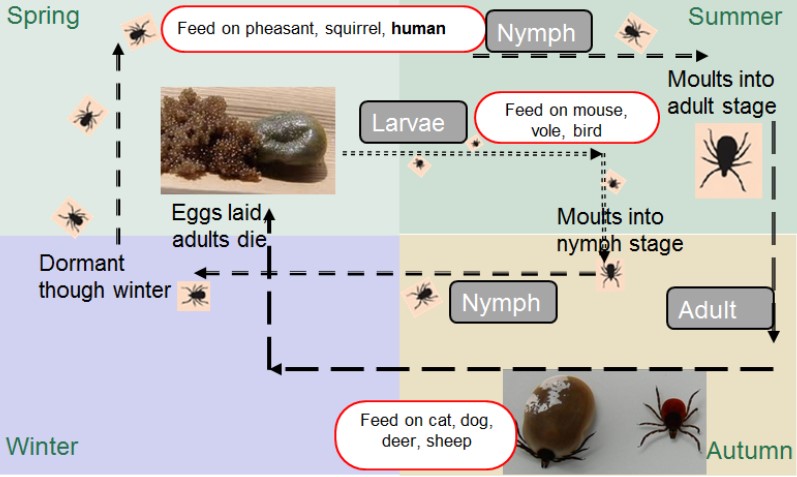

There are x4 stages to the lifecycle of a tick: egg, larvae, nymph and adult. Whilst this may sound like unnecessary additional information (and maybe it is) I think it is important to understand our enemy, especially as a tick will only feed once during each stage, growing after their meal of blood to then moult into the next stage of their life. It is when a tick is feeding, that it will pass on any disease.

Ticks like to live in areas with moist air, and a food source. This makes moorland habitats, with the ferns, rain and grazing animals/hiker a perfect environment. In order to attach to their prey, a tick will climb to the top of any foliage they call home, and latch on to any passing animal or walker. A tick bite is entirely painless, and given their diminutive size, especially in the larva and nymph stage, they can often be overlooked or unknown about.

Ticks can be active all year round, but they are most active in the months April to July, and sometimes later in the autumn. Activity continues over the winter months but at a significantly reduced level.

How to avoid a Tick Bite

There are five main pieces of advice, stolen with pride from the mountaineering Scotland site (https://www.mountaineering.scot/safety-and-skills/health-and-hygiene/ticks) that will help you avoid a tick bite, appreciating some of these are easier to apply then others.

- Avoid walking through long grass and areas of thick foliage – consider keeping to paths and tracks in heavily infested areas.

- Leave no exposed skin on your legs, feet, ankles or arms – wear long sleeves, tuck trousers into your socks or wear gaiters, choose fabric which is thickly woven.

- Spray insect repellent on clothing and socks.

- Wear light-coloured clothing so you can see the dark ticks and remove them – inspect clothing often to remove the ticks.

- Check yourself, your children and your pets for ticks when you get home, especially your hairline, navel, groin, arm pits, between toes, behind the ears and knees.

How do you remove Ticks?

Whilst avoidance is definitely better than cure, if you walk in the moors, hills, mountains, outside often enough, a tick bite is inevitable. If/when you find a tick, don’t panic. Removing it is simple enough and doing so within 24hours (highlighting the importance of undertaking a tick check when you get home) will mitigate most risk of contracting any illness.

There are two main methods for removing a tick. You can find all sorts of advice online about Vaseline, essential oils and matches/lighters, but please don’t follow these as they rarely work and can cause secondary injury. The best ways to remove a tick are:

- Use a Tick hook – these come in assorted sizes (for different sizes of ticks) and cost just a few pounds. If using a tick hook, approach from the side of the tick (where it is flat) until it is held securely in the hook. Then, simple lift the hook lightly and TURN (either clockwise or anti-clockwise) – the tick will be removed, head and all.

- Use tweezers – this is the method I had to follow. Get the tweezers onto your skin and grip as close to the head of the tick as possible. Do not squeeze too hard, as this risk pushing the blood from the tick back into your body. With firm pressure, pull upwards slowly DO NOT TWIST.

Once the tick is removed, clean the area, your hands and your removal tool.

The reason for removing ticks, aside from them being gross, is because they can (although the majority of tick bites won’t) pass on Tick Bourne Diseases, the two biggest being Lyme Disease and Tick Bourne Encephalitis (TBE)

Lyme Disease

What is it?

Lyme disease is a bacterial infection (caused by Borrelia burgdorferi) that can be spread by infected ticks to humans, if not removed in a timely manner. I want to reiterate, not all tick bites will cause Lyme disease. This is because not all ticks are infected, and not all bites form an infected tick will lead to Lyme Disease.

Lyme disease may evolve through phases (stages), which can overlap and cause symptoms that may involve the skin, joints, heart or nervous system. These stages are:

- Early localized Lyme disease (weeks one through four)

- Early disseminated Lyme disease (months one through four)

- Late persistent, late disseminated or just late Lyme disease (after four months, even up to years later)

Lyme disease is easy to treat (with antibiotics), if caught early. Whilst most people treated for Lyme Disease will be fine some may still encounter some long-term effects. Untreated Lyme disease may contribute to other serious problems but it’s rarely (but can be) fatal.

What are the symptoms?

The symptom that most people know about is an erythema migrans (“Bullseye”) rash. This rash begins around the site of the bite, and often, if untreated, lasts for several weeks. The rash usually appears 1-4 weeks post infection but may appear anywhere between 3 days to 3 months post bite, so you do need to remain vigilant after removing the offending tick.

Alongside the rash, and more likely to appear a few days after infection (and therefore may appear before the rash), some people may get flu-like symptoms including fever, myalgia (muscle and joint pain), loss of energy and headache.

If left untreated, months and even years later, patients may also experience systemic problems, including neurological problems (affecting cranial nerve, peripheral and central nervous systems), heart problems (Lyme Carditis), joint swelling and pain (Lyme Arthritis), Skin conditions (acrodermitis chronica atrophicans) and cognitive impairment.

That’s a lot of medical jargon to say that untreated, Lyme disease can be really nasty and therefore if you are suspicious of an infection, book an appointment with your GP. Now, lots of online forums will suggest this is an emergency and needs an appointment ASAP or to be seen in an Emergency Department – that’s not true and adds to an already overburdened service. It is true however that the sooner Lyme is treated the better so an urgent appointment (within a week of concerns) would be entirely reasonable.

How is it treated?

Patients diagnosed with Lyme Disease will be given antibiotic treatment. The choice of antibiotic is based upon the presenting symptoms, but essentially anyone who is diagnosed with Lyme disease will be given oral Doxycycline (or amoxicillin if doxy can’t be given for any reason or oral azithromycin if penicillin allergic). Antibiotic treatment is usually for 28 days (which considering most people get Lyme Disease in the summer, and doxycycline can may you overly sensitive to sunlight is a real annoyance).

Of note, anyone with focal symptoms (neurological, cardiac etc) will also need referral onto a specialist and will likely receive intravenous (into a vein) antibiotics alongside the Doxycycline.

Tick-Borne Encephalitis

The other disease often (loose term for the word since it is rare) spread by ticks is Tick-Borne Encephalitis (TBE).

What is it?

Tick-Borne Encephalitis is a viral infection spread by tick bites but the risk of this in the UK is extremely low.

What are the symptoms?

Most people who contract Tick-Borne Encephalitis will not have any symptoms. Symptoms tend to appear (in some patients) about a week after getting bitten and for most symptomatic patient, Tick-Borne Encephalitis causes flu-like symptoms:

- Fever

- Tiredness

- Myalgia (muscle pain)

- Headache

- Feeling sick

The symptoms usually go away on their own, but in a few people the infection spreads to the brain and causes more serious symptoms a few days or weeks later including:

- Stiff neck

- Photophobia (intolerance of bright lights)

- Seizures

- Cognitive issues and slurred speech

- Paralysis in some parts of the body.

How is it treated?

There is no specific treatment for Tick-Borne Encephalitis and therefore, any treatment given is supportive (e.g. analgesia for any pain).

If systemic features are developed (those listed immediately above), emergency treatment will be required.

There we go then, a post all about the disgusting little creatures known as Ticks. Whilst this topic isn’t particularly pleasant, it is important that avid hikers are aware of what ticks are, how to prevent a tick bite, how to remove ticks and what illnesses they can cause and as such, I hope this post is helpful in some small way.

Leave a comment